A Motley Landscape: How Films Travel

What is the capacity of filmmakers, almost a hundred years later, to show their films? Are they modern-day pilgrims, who diffuse their work personally, or are there ways to let the film travel for them? A finished film only starts to exist when it can be shown. And what we learned during the On & For Distribution Models meeting (April 2019, Brussels) is that there are a multitude of different approaches to making a film present and to preserve its existence in the future.

Five distribution platforms were invited to talk about their work. In this text, I will report on their presentations. The speakers of the day were María Palacios Cruz of LUX, Sirah Foighel Brutmann of Messidor, Gerald Weber of sixpackfilm, Diana Tabakov of Doc Alliance and Niels Van Tomme of ARGOS.

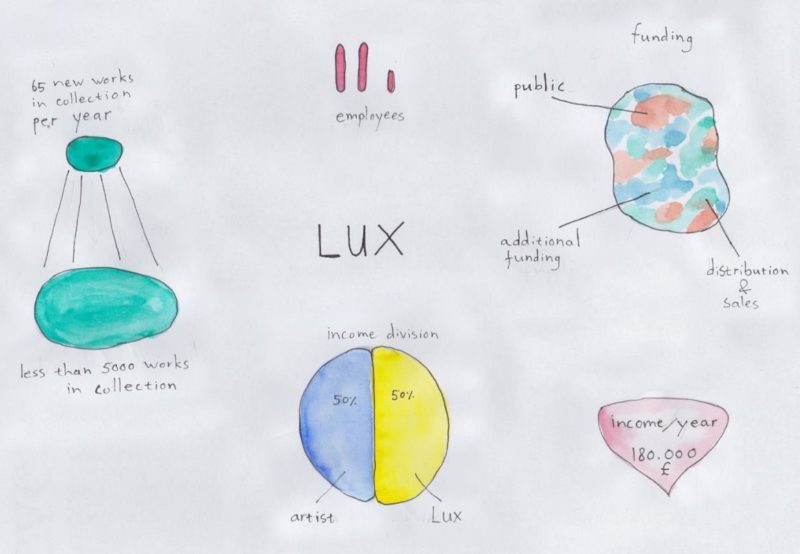

LUX

María Palacios Cruz is part of the British distribution platform LUX. Their building is situated in a park in London, and besides the offices, it accommodates an exhibition space and a publishing house. They support researchers, students and artists.

With glowing eyes, Palacios Cruz explained how most of the work of a distributor is invisible. A lot of what they do doesn’t result in anything. Behind the scenes, they write letters, visit festivals or museums and have conversations with programmers. All these actions create a tissue around the films, and even though it doesn’t often result directly in a screening or exhibition, the films exist. When people keep hearing and reading about works in LUX’s collection, at the right moment it will germinate and something will grow out of it.

LUX started as a filmmakers’ collective. That is why they do not distribute a single work. They distribute an artist. This means that the moment they decide to add an artist to their collection, their whole oeuvre will be included, so they welcome masterpieces as well as less successful works. For them it is important to have this bond of confidence with artists, which is more important than with the individual art film.

For every screening, a fee is requisite. Even though the work of the artist is created with passion, and even though it often feels wrong as an artist to capitalise upon your labour of love, this basic rule is necessary to be able to continue working.

Here, Palacios Cruz quotes Hollis Frampton’s letter to the then director of the Museum of Modern Art in New York, expressing that his ability to produce art ‘cannot continue on love and honor alone’. The director had invited him to present a retrospective saying that ‘there is no money involved whatsoever’.[1]

There are not many people working in this economic system who have to struggle with the extreme ambivalence of making a living with work that has grown out of passion other than artists. When an artist wants to survive, they have to learn to exploit their love. And this makes it hard to negotiate something like rental fees without feeling a sense of ill-treatment towards oneself and one’s art. This ambivalence is preyed upon by many.

But as Frampton points out in his letter, he generates wealth for scores of people by making his work, so why, he asks himself, should he be the only one not being paid for the show?

I’ll put it to you as a problem of fairness. I have made let us say, this or that many films. That means that so and so many thousands of feet of rawstock have been expended, for which I paid the manufacturer. The processing lab was paid, by me, to develop the stuff, after it was exposed in a camera for which I paid. The lens grinders got paid. Then I edited the footage, on rewinds and a splicer for which I paid, incorporating leader and glue for which I also paid. The printing lab and the track lab were paid for their materials and services. You yourself, however meagrely, are being paid for trying to persuade me to show my work, to a paying public, for “love and honor”. If it comes off, the projectionist will get paid. The guard at the door will be paid. Somebody or other paid for the paper on which your letter to me was written, and for the postage to forward it. (Frampton, 1973)

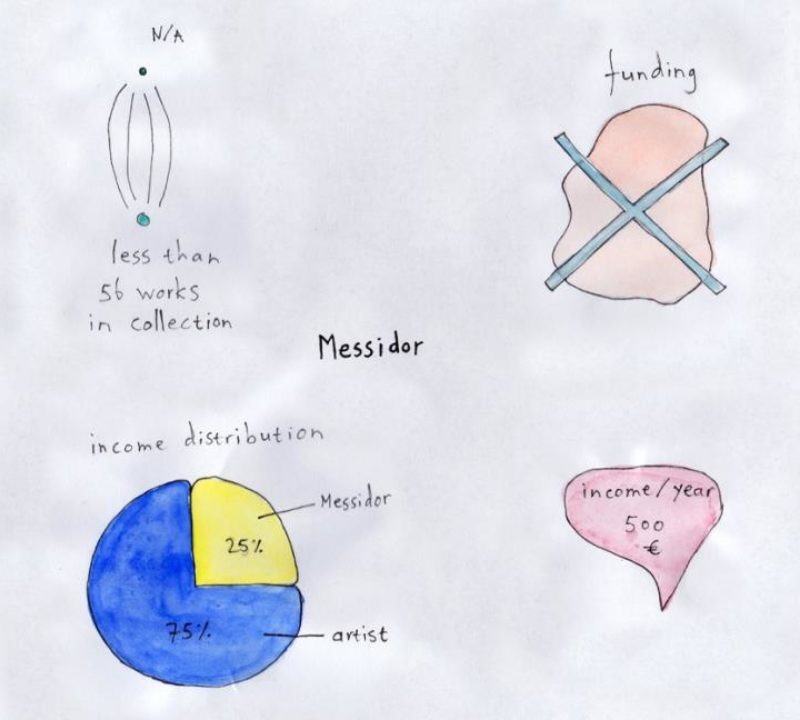

Messidor

This brings us to the second speaker, the filmmaker Sirah Foighel Brutmann. She collaborates in a collective called Messidor, together with Meggy Rustamova, Pieter Geenen and Eitan Efrat. They found each other through mutual interest in each other’s work. They make not only films, but also installations, photographs and other work. They received a working grant to come together as an artist-run organisation, which meant they started working in the framework of a not-for-profit organisation. The artists in Messidor are facing the same problems as Frampton did in 1973 when he wrote his letter to the curator of film at MoMA.

In some ways things are worse now than before, as the festival industry has discovered that there are many filmmakers who distribute their own work. Some festivals consider filmmakers as the consumers, even to a larger extent than the eventual audience. They build their business model around the dreams of filmmakers, rather than the love of cinema. In some cases, collecting submission fees has become the sole ambition.[2] With the democratisation of film production, the game of supply and demand has tilted to the disadvantage of independent filmmakers.

Foighel Brutmann said: ‘When we started to distribute our own work, we thought that we could just send our films to festivals and they would be screened. But this has changed over the last ten years. Now, small-scale films are being marginalised. Festivals have started to ask increasingly larger submission fees. We decided that we didn’t want to pay festivals just to take a look at our work. So we got in contact with festivals, proposed our films and explained we weren’t ready to pay them. We made a lot of friends. We also made a lot of enemies.’

It is not easy to arrange a good premiere, but it’s equally hard to keep the film alive. Two or three years after the production has been released, most festivals won’t be interested to show the film, when it has lost its novelty. Several of the distribution platforms, like sixpackfilm or LUX, often show films in retrospectives. But as María Palacios Cruz acknowledged, there is an ‘undistributed middle’ between premieres and the canon. She proposed that the role of the distributor could be to ‘undo the canon, instead of trying to introduce new work to it.’ The collection of a distributor tells a story besides that of the official canon, which is just another story, albeit one more influential. When making the selection for their collection, LUX addresses the voices that have remained unheard, that are often overlooked or ignored. ARGOS, for their part, observed that films have a longer life expectancy in art spaces, which are less focused on premieres and which also provide more possibilities for an audience to see the work. Instead of one or two screenings in regular festivals, a work may be visible for several months.

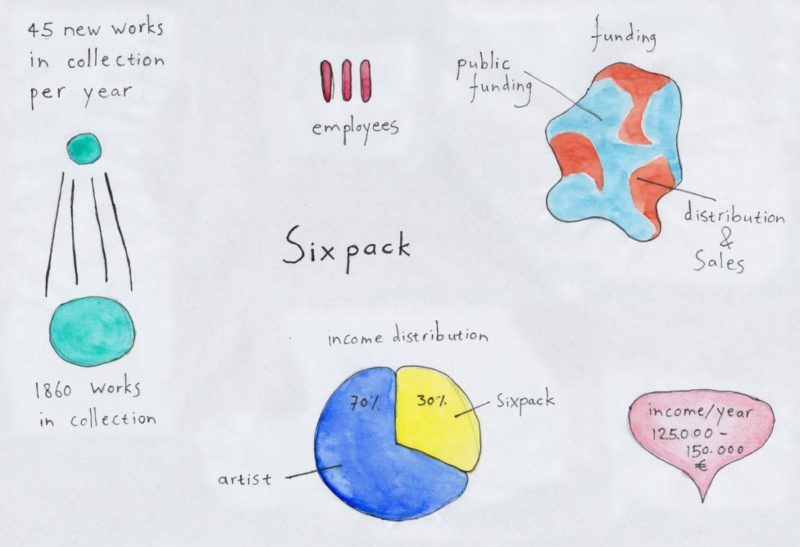

sixpackfilm

Gerald Weber spoke on behalf of sixpackfilm, an Austrian non-profit distribution organisation. Artists can submit their films to an open call four times a year and may be chosen by a committee. Sixpackfilm distributes new and old Austrian films to festivals, but also to cinemas, for exhibitions and for television broadcasting, although the possibilities for broadcasting are diminishing. Television channels tend to buy films at an early stage of production and are less often willing to invest in a film that is already finished.

Indeed, filmmakers today have witnessed how the age of television has passed. Television channels are rarely willing to take financial risks. They favour safe and accessible works rather than films with non-standard formats or with a personal voice. In this regard the film by Geoff Bowie, The Universal Clock: The Resistance of Peter Watkins (2001), in which Watkins takes a critical look at the ‘content production facilities’ that television channels had become is interesting. While visiting a conference on television formats, the head of National Geographic memorably confesses that they had found the best way to keep the audience glued to the programme without giving them any new information. The structure and editing is optimised for the best ‘cliffhanger’ before the commercial break. The director has to respect the rules and time slots that are premeditated for each format. As the head says himself: ‘I completely respect it if a filmmaker wants to keep his own artistic voice. But we won’t hire him then.’

Since 2001, when this interview took place, there are no signs that television has evolved towards a rejection of the ‘universal clock’-mode. It even seems keener to cling to formatted content as if it’s the last straw. Neither have big players like Netflix created much breathing space for independent filmmakers. But the story of television is not finished. There are still filmmakers who are funded by television channels. Even though it demands a different method of working with co-productions, filmmakers should not turn away from the medium.

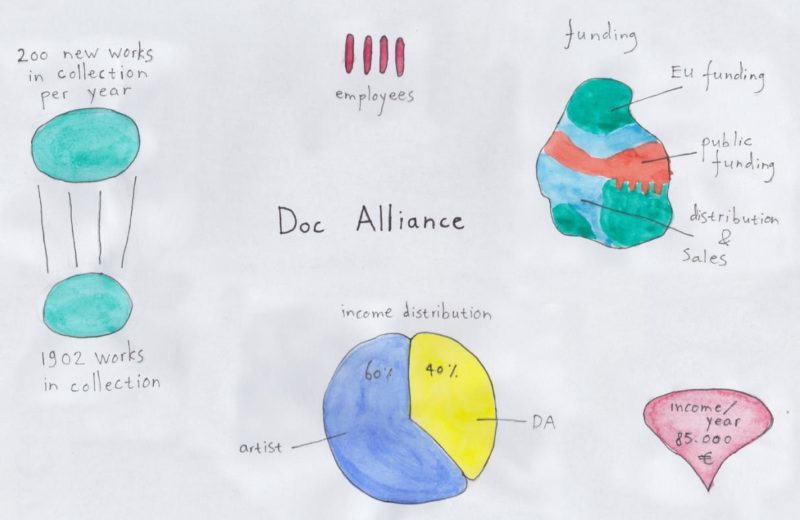

Doc Alliance Films

While television is regarded as a thing from the past, VOD is widely seen as the future of film distribution. Diana Tabakov came from Prague to talk about Doc Alliance Films. Before she started her presentation, she showed a short trailer, in which film images were projected into cardboard boxes which were folded and composed to create a showing device as delicate as a musical box. It presented the platform as a pliable space, as a soft image-machine. Doc Alliance makes different ways of screening possible, since watching a film online is no longer place-related. Besides the wide screen in a big space where people watch a film in a crowd, a film can also be snuggled on one’s lap, it can travel along in a train while landscapes rush by or it can be projected onto an unfolded blanket in the living room. Set free from the cinema hall, film has become something that can be so small as to fit in one’s pocket.

Doc Alliance works together with a number of big festivals: CPH:DOX, DocLisboa, Docs Against Gravity FF, DOK Leipzig, FIDMarseille, Ji.hlava IDFF and Visions du Réel. All films that are selected at those festivals will automatically be included in the collection. Besides the selections of these festivals, Doc Alliance also selects other films to be included in curated programmes like ‘festival focus’, ‘retrospective’ or ‘films of the week’. It is available around the world, but they may also geo-block, for example, when a festival in a specific country demands the film never to have been shown before in their area. So, even in an online environment, locality is still important. Tabakov also observes that audiences mostly look at films that are made in their own country. Despite the American hegemony in pop culture, there is still a high level of interest in national and local film.

But at the same time, it is often difficult to bring films outside of cities. In many European villages, it is much more difficult to mobilise an audience. As Tabakov put it, ‘Because the infrastructure is often not there, but also because there is a lot of work to be done regarding film literacy.’ And here lies a key task for education: to teach children and youngsters from all backgrounds to look at cinema as an art form, and to become acquainted with its multifaceted shapes. So even when an online platform makes cinema available to the most remote lands, reflecting on and exchanging ideas about cinema is a precondition for it to thrive. Several distributors mentioned that they are engaged in this. For example, ARGOS runs weekly film workshops for children from their neighbourhood in the centre of Brussels.

Argos

In his presentation, the last speaker advanced another perspective on the work of the artist and the distribution of their work. Niels Van Tomme from ARGOS presented a utopian vision in which he contemplated the strategy of just walking away.

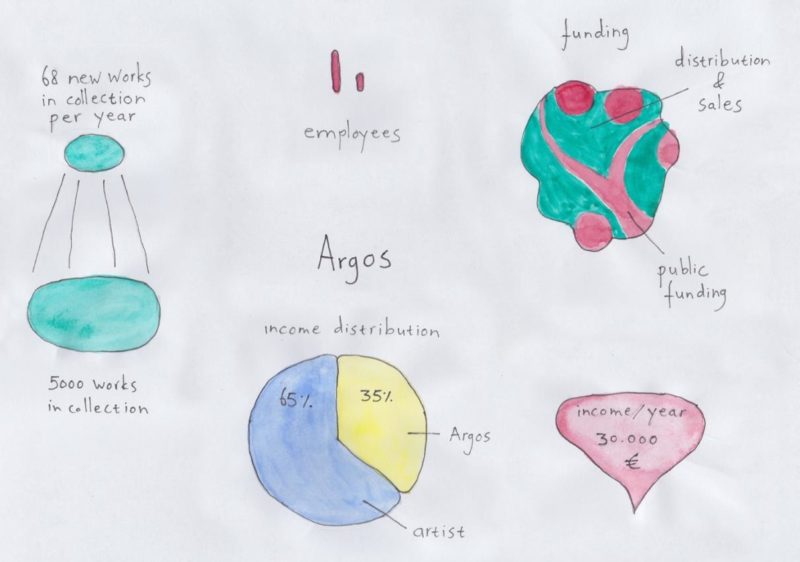

ARGOS is based in Brussels and focuses on art film. They cover the entire chain of development, production, archiving and preservation (both analogue and born digital), and distribution. They have a large space that hosts multimedia exhibitions. They support artists by putting production and editing facilities at their disposal. Besides this, they’ve built a collection of around five thousand analogue and digital works that can be consulted by the public in their media library. About one third of these are in active distribution, which means that the films are sent to festivals and venues. The other two thirds are available for screening, but will be sent out only on demand.

Revisiting the precarious situation many filmmakers are in when trying to get their work seen, he cited the novel Walkaway by Cory Doctorow, which is set in a future where some friends decide to walk away from a dysfunctional society. In their new settlement, they think of strategies to create a new society—and beat death. Van Tomme asked himself: ‘What if distributors would walk away from the distribution models that are dominant today? If they would walk away from festivals that refuse to pay screening fees, and from institutions that "forget" to pay artist-fees?’

In the novel, there is a proposal for a ‘datafication’ and ‘platformisation’ of many aspects of society. The characters develop a digital platform that is designed for mass collaboration. This platform is imagined as an anti-capitalist space for free exchange and free collaboration. There is no centralised power, since everyone shares the same amount of power.

Inspired by Doctorow’s utopia, Van Tomme added, ‘Can we build a collective distribution platform? Go away from the centralised structures we are all engaging in right now, and operate on an equal platform in which artists, distributors, festivals and consumers will benefit equally?’

Before going outside

Just like Van Tomme, most distributors believed in the future of online distribution, even though Diana Tabakov remarked that it has already been the future for the last ten years. But at the same time, the magic of watching a film in the cinema cannot be underestimated. In his text ‘Leaving the Movie Theater’,2 Roland Barthes describes the intimate and even erotic experience of the audience who ‘slides down into their seats as if into a bed’. After walking through the streets, the spectator can find this sensual yet neutral space where their imagination may glow: ‘It is in this urban dark that the body’s freedom is generated; this invisible work of possible affects emerges from a veritable cinematographic cocoon; the movie spectator could easily appropriate the silkworm’s motto: Inclusum labor illustrat; it is because I am enclosed that I work and glow with all my desire.’

The darkness of the cinema is the absolute opposite of the television, Barthes writes: ‘here darkness is erased, anonymity repressed; space is familiar, articulated (by furniture, known objects), tamed [...]: the eroticization of the place is foreclosed: television doomed us to the Family, whose household instrument it has become—what the hearth used to be, flanked by its communal kettle…’

Cinema should not be tamed. It should stay wild, travelling in the open, often vulnerable, sometimes unnoticed. What if an image can become like the fire in the hearth that unites households, but that which can also disrupt domestic spaces, with fierce flames that escape and spread like a running fire? Each of the distributors showed there are many ways to spread film culture, acknowledging the transformative power of context. A film shown on a laptop is not the same as a film shown in an exhibition space, nor is it the same when shown in a community centre. The film resonates differently each time.

And even though a film can lie dormant when it has passed through the momentum of novelty, distributors and artists alike are committed to redrawing the landscape of cinema culture and creating a fertile ground on which films will retain a presence. To walking away from the monoculture of a yearly harvest that leaves bare ground and to cultivating sustainable cinema distribution in which films of all sorts will continue to thrive.

Nina de Vroome is a filmmaker. She is a writer and editor for Sabzian. As a teacher she is involved in various educational projects. All drawings are by the author Nina de Vroome