To All the Lost Tapes

To all the films that were made and lost. To the failing hard drives, lost tapes and cassettes, unreadable with today’s technologies. Erased memory cards and overwritten memories. To the films stacked on archive drives, burnt on DVDs, scratched by the years. To the copy–pasted Vimeo links and their lost passwords. To a film’s shorter and shorter lifespan.

To all the films yet to come, shot and edited, which will be lost soon thereafter. To those neither selected nor shown, to those which will never meet their audience. To the films that are only seen within close circles, and those that will never cross borders. To the films that only knew international festival networks and never came back to their native roost. To the V1, V2, V3 edits, to the multiscreen projects that remain invisible without a space to show them. To the first, second and third films hidden behind a properly produced first film. To the lost tapes yet to come.

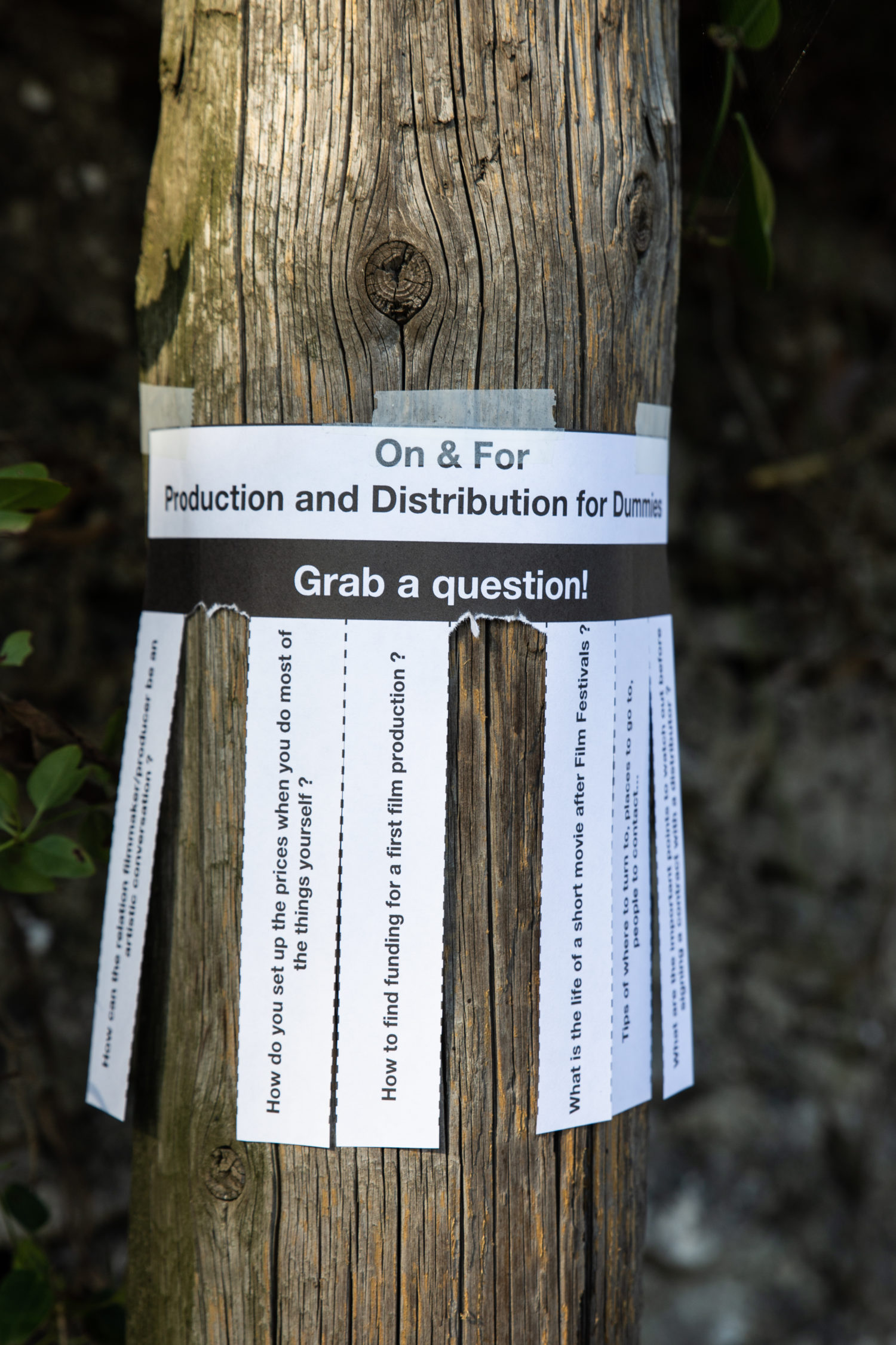

A term often used in the music industry, LPs labelled ‘lost tapes’ are re-releases of previously published material. They are (re)discovered by digging into crates and drawers—all in order to give a second life to tracks that didn’t meet success in their time. Particularly cherished by aficionados, collectors, and vinyl-diggers, the lost tapes end up not being quite so lost for those who look for them. They might, however, remain lost and forgotten to a wider audience for the reason that they were released too late to still be expected or too early to be anticipated. The lost tapes’ fate came to mind when reading the questions posed by the Dummies participants, lost and found questions. Those that did not find an answer. The kind of questions one used to have to solve on one’s own, years ago now, do you remember?

From the outset, it might be tempting to see the lost tapes syndrome as a two-sided pharmakon—a blessing for films that were saved from dusty cupboards and shot to stardom years later, and a curse for the tapes that remained ‘unfound’, seemingly unfit for our times. For the lost tapes to be able to speak for themselves, they require us to lend an ear to the stories they tell. Beyond their stories, however, the Dummies-questions similarly make interrogations to unfold and attend to.

Indeed, when approaching these questions, there lies a temptation to read them as fragments of a bigger picture. When sequenced, ordered into categories that fit, these questions assemble a landscape of the current context of creation for young filmmakers.

However, one should not transform these questions into something other, and let them speak for themselves: ‘which funding methods or institutions are available for films in auto-production?’ does not necessarily mean ‘I want to keep working by myself and I don’t trust production’. Instead, it may suggest that one does not wish to wait for years for a green light to be able to make a first shot; that perhaps one has networks of collaboration at hand that bypass institutional ways of production; that one might have invented for oneself solutions to prevent funding from being the deciding factor for a project. Additionally, these questions stem from the questioning of whether to remain ‘independent’, a desire encountered many times in the pool of questions; a desire to be able to shoot as soon as possible.

Through ‘How can I diffuse an artistic film?’, you might read, ‘I made a film on my own, but how do I show it beyond the circle of my peers?’ ‘How to make the most sustainable film (with a very low budget) while still making sure it is done well enough to be considered seriously?’ might sound like, ‘How can I access the visibility I aim for without changing the way I make films?’ Through these questions, however, blows a fresh wind for a third way between the cracks, a defiance in an established system of visibility. That is to say, finding some help to film what needs to be shot, and be able to present it whenever it’s finished and whenever it makes sense—visibility, recognition, expectations, notions that seek to be challenged through these questions, and alternative routes to be found by the upcoming generation(s) of filmmakers.

‘What kind of new models of production can we envision today?’ As the collected Dummies-questions indirectly look back on and crystallise a state of affairs, in a similar fashion, films encapsulate the conditions and accidents that led to their making. Material means, travelling expenses and insurance, extra rolls of film, unpaid collaborators and actors paid only for a few days. A film is the product of both contingency and given material/emotional conditions, in short: production means. The Dummies-questions carry a similar burden. These questions (like the lost tapes) are affected by the tremendous efforts required for bringing them into being. They further solidify—and thus reveal—the social relations of a precise moment in history, helping us to retrace the making of a cultural narrative. At a very peculiar time in filmmaking (due to the production shutdown enforced by the pandemic), the Dummies-questions find a shared space to learn from and to give voice to in the On & For workshops. The Dummies workshops aim to be a place of exchange between filmmakers, and for anyone who wishes to participate and assemble. They attempt to untangle the convoluted routes to funding and open up the complex logics of access, to make room to reassess what help, support and funding really mean.

How does one know if a tape is already lost when finishing one’s film? As most of us know, or might just even guess, it is becoming increasingly difficult to get into international festivals. One who is eager to send their tape takes the risk of being turned down, and must comply to have their film concealed if selected, keeping the international premiere label untouched and intact for however many months until then. The lucky ones this year were screened online, under lockdown circumstances, before a wide, international (that is, if the festival isn’t geo-blocked) but anonymous audience—the trade-off for the reward. Is this really the most rewarding outcome for filmmakers? This festival system has produced such a turnover in festival applications that tapes end up having a tacit two-year life expectancy for festivals; waiting their turn at the expense of screenings in smaller venues, online or in the flesh, and making festivals compete between themselves to get international premieres, assuring success only for more ‘career-driven’ filmmakers.[1] This poses a real question about visibility and recognition, and asks for a new positionality. Reassessing the value of international festivals themselves as the aspirational prime public, to the benefit of situated and contextualised screenings, could help foster a local community of filmmakers, local scenes and local production structures; shifting priorities might be the response to 2020—and the years to come.

Mechanisms such as these expose the dangers of the ever-expanding factory of lost tapes, for which such trade-offs might not be worth the risk. How can the Dummies, then, not wish for a third way to make their tapes seen and their questions heard, narrowly escaping becoming lost themselves? When a tape deemed to be lost is made visible anew (or at all), a particular moment occurs: a sigh of relief stems from this lapse of invisibility, an incomparable joy is to be felt when the tape brings together a venue and an audience. Simply put, a common pleasure lies in sharing a film or a question at the right time and place.

A glance at the Dummies-questions through this lens makes it blatantly visible that these mechanisms have been identified by not-so-Dummy filmmakers after all.

From the Dummies, we hear the need for spaces without limiting conditions, shifting the rules of visibility, recognition and mutual support towards diverse and viable alternatives. Spaces such as the On & For workshops for production and distribution are crucial in unveiling routes for support and sharing information, so too are DIY groups and workshops for sharing know-how and developing grassroots cooperation,[2] local institutions for organising open screens,[3] film programmes, and supporting artists-in-the-making, semi-private screenings in artists’ studios.[4] It is perhaps down to each Dummy, practitioner and organiser, facilitator and participant, to keep the cracks open,[5] in between which we can exchange, and debate how we want our films to be valorised and accessed. Redefining for ourselves what support and funding really mean, what exposure and recognition really entail; how expectations can be plural.

On and for whom?

It is the semi-visible tapes that we would like to honour through these words, to reflect on film’s differential publicness and access points. Tapes that ought to find their way, and eventually shed light on distribution and production blind spots, their flaws carried within the material itself and expanding into its community: there will always be more films created than there will be selected, supported in production and distributed—more questions asked than answered.

Giving the floor to the Dummies themselves, and working from their questions, helped to shed light on these entangled issues, and gives a particular traction and actuality to the lost tapes conundrum. There lies a need for such a discussion and a need to create visibility for lost tapes, to negotiate new terms for creation in increasingly deranged times.[6] Here lies my position, alongside that of On & For’s initiative, as an attempt to deal with the questions raised. Perhaps not to answer them all, most probably not, but surely to hear them ask other questions in return, so the questions circle back.

Maxime Gourdon is a curator, researcher and occasional cinematographer based in Brussels.

Image: Artistic intervention courtesy of the artists Juliette Le Monnyer and Maxime Gourdon.